The tricky business of building a code of conduct for AI

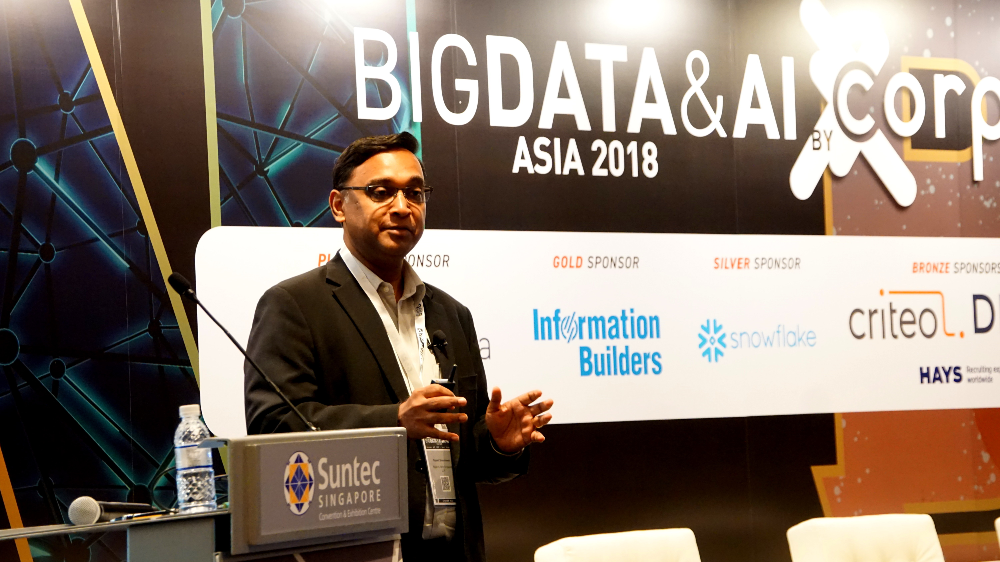

The fact that artificial intelligence (AI) is capable of learning puts it at risk of internalising society’s prejudices. Left unchecked, AI could encroach on privacy and undermine social values. Ethics and transparency are therefore crucial in the development of AI, said lawyer Mr Rajesh Sreenivasan at the Big Data & AI 2018 conference.

A certain degree of irony exists in the fact that not one, but two anti-communist chatbots were spawned in China. Innocuously named ‘Baby Q’ and ‘Little Bing’, the two chatbots were released in 2017 on Tencent QQ, a popular messenger app in China.

Originally intended for answering general knowledge questions—say, “What’s the weather like today?”—the chatbots drew ire from the ruling Chinese Communist Party when they began denouncing the Party as “corrupt and incompetent”. Baby Q and Little Bing have since been erased from existence, but their fleeting encounters with the Chinese public were a revealing case study of how artificial intelligence (AI) can be influenced by the people it interacts with.

“You don’t have to hack a bot—it is constantly learning [through AI]. You just need to understand how it learns and teach it in such a way that it absorbs what you are telling it. [The bot] then starts to express the same prejudices as you,” said Mr Rajesh Sreenivasan, head of technology, media and telecommunications at Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP, speaking at the Big Data & AI 2018 conference on 4 December 2018.

A focus on ethics and transparency

Bots have also been ‘taught’ by the public to be racist or sexist, added Mr Sreenivasan; the legal question is: whose fault is this? While there are no straightforward solutions to issues such as the legal liability of a racist bot, Mr Sreenivasan noted that society has begun to acknowledge the need to draw up ethical standards and regulations surrounding the development and use of AI.

For instance, the Partnership On AI consortium, consisting of AI technology companies, academics, researchers and civil society, has been established to formulate best practices on AI technologies.

In Singapore, the Advisory Council on Ethical Use of AI and Data has been tasked with creating reference governance frameworks and publishing advisory guidelines for adoption by the industry.

Emphasising the need for a “technology-neutral and light-touch” approach to regulating AI, Mr Sreenivasan highlighted two principles that have been established to guide AI development. Firstly, AI and data analytics (AIDA)-driven decisions should be held to at least the same ethical standards as human-driven decisions. This is arguably tricky to assess and abide by, which brings the second principle into focus: transparency.

“Transparency doesn’t mean giving away the secret sauce… you retain some of the intellectual property (IP), such as the algorithm, but you must be transparent on two key areas: what data is used and how the data affects the [AI’s] decision,” he explained.

Balancing innovation and regulation

Still more legal conundrums arise around works created by AI. Here, the question is whether or not such works constitute IP, and if so, who has claim to it. According to Mr Sreenivasan, “A compilation of facts and data may be protected if it constitutes an intellectual creation, by reason of the selection or arrangement of its contents.”

Hence, if an AI collects, compiles and processes data about end-users to present a report about user behaviour, does this constitute an intellectual creation? “The argument is yes because at that point, the data has been collated in a unique manner, such that the bot is able to understand it as a question and respond to it with an answer. Therefore, it is, in fact, IP,” explained Mr Sreenivasan.

And because IP can be created from data, users should have the right to decide on when their data is being collected and how their data is used. This is where Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Commission has stepped in to propose an accountability-based framework for discussing ethical AI governance and human protection issues in the commercial use of AI.

While such regulations may stifle innovation in AI to some degree, this cost is something Mr Sreenivasan is willing to accept, he said. “In my view, it is a price well worth paying because the risk of a completely unregulated bot-space, or AI-space in the broader sense, is not acceptable,” he concluded.

https://www.tech.gov.sg/media/technews/the-tricky-business-of-building-a-code-of-conduct-for-ai